The Surprising History of Scarsdale's Black Community

- Tuesday, 27 October 2020 15:37

- Last Updated: Tuesday, 27 October 2020 17:01

- Published: Tuesday, 27 October 2020 15:37

- Joanne Wallenstein

- Hits: 2906

With the issue of race in the forefront, Scarsdale attorney, teacher and historian Jordan Copeland has produced a fascinating video highlighting his research on the Black community in Scarsdale, from slavery to the modern era. Originally delivered as a public cosponsored by the Scarsdale Forum, Scarsdale Public Library, and Scarsdale Historical Society, the video is posted on YouTube and can be viewed here:

With the issue of race in the forefront, Scarsdale attorney, teacher and historian Jordan Copeland has produced a fascinating video highlighting his research on the Black community in Scarsdale, from slavery to the modern era. Originally delivered as a public cosponsored by the Scarsdale Forum, Scarsdale Public Library, and Scarsdale Historical Society, the video is posted on YouTube and can be viewed here:

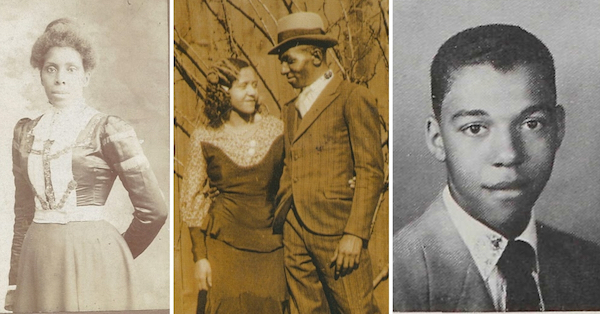

The research includes historic photos, documents, maps, newspaper articles and live interviews with the descendants of Scarsdale’s first black residents Black people who grew up in Scarsdale from the 1950’s to 80’s. They paint a portrait of a strong Black community which has been an important part of Scarsdale but has not always been fully accepted.

He begins with the story of Scarsdale’s earliest Black residents who were two thirds of Scarsdale’s population in 1712. In fact, Thomas Hadden, the first owner of what is now Wayside Cottage and 150 acres of land, had three children with his wife and another five with his slave or “wench Rose” who he provided for in his will at the time of his death in 1762.

As evidence, Copeland shows a set of murals that is still displayed in the Scarsdale Post Office that depicts the formation of Scarsdale in 1701 when Caleb Heathcote bought the land from the widow Richbell. The mural includes one slave tending to a horse.

As evidence, Copeland shows a set of murals that is still displayed in the Scarsdale Post Office that depicts the formation of Scarsdale in 1701 when Caleb Heathcote bought the land from the widow Richbell. The mural includes one slave tending to a horse.

Though discrimination was not unusual throughout Village history, Black children were permitted to attend school with their white peers, which was highly unusual. He shows several school photographs, including a one room Quaker School in the 1890 and another of the students of the Griffin School in the 1920’s. Both pictures show both white and black children and adults in attendance at school and the building that housed the Griffin School remains today on the grounds of the Quaker Ridge Golf Club.

By the 1930’s, Scarsdale’s Black population had grown to 482, but many were living in white households as maids, butlers and chauffeurs.

One of neighboring Edgemont’s first Black homeowners ended up in court. Joshua Cockburn, a wealthy steamship captain purchased a tract of land in what was known as “Edgemont Hills.” He built a Tudor style home there in 1937 but was sued because the covenant on the land barred black homeowners. A neighbor feared that Black families would harm their own real estate values. Cockburn was defended in court by Thurgood Marshall but lost the case. Despite the defeat he remained in the home because the decision was not enforced.

Copeland shows that Blacks did not significantly participate in Scarsdale’s transition from an agrarian to a suburban community. Even as late as the 1960’s, Blacks met discrimination when attempting to purchase homes in Scarsdale.

Copeland includes an interview with Joretta Evans Crabbe who shared what happened when her parents tried to buy a home in Scarsdale in 1969. They went into contract to purchase a home in Heathcote without meeting the current owners face to face. When the sellers realized that the buyers were Black, the homeowner called Crabbe’s father and asked him to back out of the deal. He said, “My wife is threatening to kill herself and pull up all the plants if we sell it to a Black family.” He then offered the buyers $10,000 on a $40,000 house to back off, but her parents refused. Black and White Students at school in the 1890's

Black and White Students at school in the 1890's

This is just one of the scores of revealing stories that Copeland elicited in his hours of interviews with current and former black residents of Scarsdale.

Here are a few quotes from others who shared what it was like to grow up in Scarsdale.

"We had wonderful friends who were white – but we were “other.”

“I didn’t go to my prom because there was no one to invite me.”

“I had to work twice as hard to be half as good.”

“What was hard, was not coming from a family with money.”

Some of the listeners who posed questions to Copeland during his presentation hosted by the Scarsdale Forum asked if he would seek changes based on his findings. One wanted to know if streets like Cornell and Griffin that were named after slaveholders should be changed. Another asked if the mural at the post office should be taken down. Copeland made it clear that his purpose for now was to uncover Scarsdale’s history rather than to proscribe change.

Copeland is continuing his research and welcomes input. He has set up a discussion and avenues for people to learn more, take action, and support each other. If you are interested, please fill out this form.