Former Public Defender Uses Her Experience to Inspire a Novel

- Sunday, 06 March 2022 11:06

- Last Updated: Sunday, 06 March 2022 17:17

- Published: Sunday, 06 March 2022 11:06

- Joanne Wallenstein

- Hits: 2911

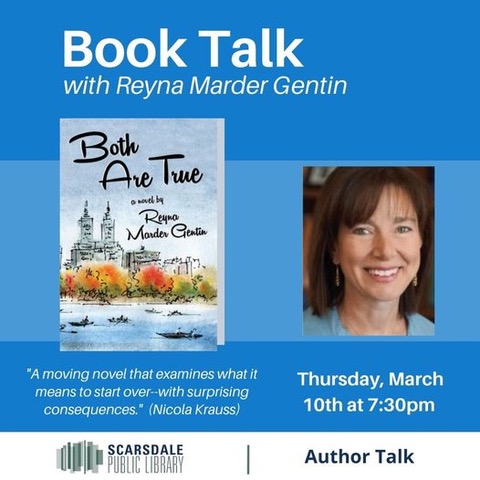

Local author Reyna Marder Gentin has just published her third book, Both are True, and will speak at the Scarsdale Library on Thursday night March 10 at 7:30 pm. Register here:

Local author Reyna Marder Gentin has just published her third book, Both are True, and will speak at the Scarsdale Library on Thursday night March 10 at 7:30 pm. Register here:

Gentin is a lawyer who left her practice as a criminal appellate attorney in the public defender’s office in 2014 and decided to try something new. She enrolled in a writing class at The Writing Institute at Sarah Lawrence College and used her work as a public defender to inspire her work. She published her first novel, Unreasonable Doubts, followed by My Name Is Layla. Now with Both Are True, Reyna has returned to women’s fiction, the law, and New York City.

About her life in town Gentin says, “My husband and I moved here 25 years ago, when we were expecting our first child. One of our favorite parts about living here is the small-town feel of our neighborhood. Across from our house is a small pond situated on a grassy green, and I love when the weather warms up and the ducks return. Our children looked forward every year to the annual picnic in the spring, where the streets are closed off and a neighbor leads the kids in relay races, a tug of war, and an egg toss. One year there was a thunderstorm right in the middle of the picnic, and we sheltered the neighbors on our front porch until the rain passed. Now that the kids are grown and living on their own, we all look back so fondly on the time we’ve spent together here.”

We asked Gentin if we could share a preview of Both Are True with our readers and here is what she shared. Explaining the story she said:

Judge Jackie Martin's job is to impose order on the most chaotic families in New York City. So how is she blindsided when the man she loves walks out on her?

Jackie Martin is a woman whose intelligence and ambition have earned her a coveted position as a judge on the Manhattan Family Court-and left her lonely at age 39. When she meets Lou Greenberg, Jackie thinks she's finally found someone who will accept her exactly as she is. But when Lou's own issues, including an unresolved yearning for his ex-wife, make him bolt without explanation, Jackie must finally put herself under the same microscope as the people she judges. When their worlds collide in Jackie's courtroom, she learns that sometimes love's greatest gift is opening you up to love others.

In this scene, we see Jackie on the bench as she presides over a case where a mother is charged with neglecting her children.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

“What’s on tap, Angela?” Jackie perused the docket sheet, but she was never good with names. The list was a long litany of abandonment, abuse, domestic violence, drugs, neglect, juvenile delinquency. Only once in a while did Jackie preside over something happy, an adoption or a family reunification. In the short time she’d been in the job, she’d come to recognize that although she did her best to discern the underlying dynamics of each situation, to be decisive and fair, much of the time she had little idea what was really going on. And even less ability to fix the problems. It was a state of affairs that would make any control freak’s skin crawl.

“All continued hearings on cases you’ve already seen,” Angela said. “Only one new matter, Clark. A neglect. Here’s the petition.” She pulled it up on Jackie’s monitor.

The charges named only the mother, Darlene Clark. The fathers were often missing in action, as though these troubled families had sprung from a vast maternal pool without any male input. Jackie had calculated the percentage of her docket that involved single moms and it was staggering, although the cause and effect wasn’t clear. Were the children neglected or turning to crime because they had no male role models, or did the fathers abandon ship when the situation at home became unsalvageable? Either way, the mothers were often left holding the diaper bag.

This mom, Darlene Clark, was accused of neglecting her two daughters, ages seven and five. According to the Department of Social Services, Clark had failed to ensure the girls’ attendance at school, not taken them for routine medical care and inoculations, and not fed them sufficiently. The allegations were serious but didn’t rise, yet, to the level of abuse. Maybe with intensive court-ordered support and education, Ms. Clark could turn this around. Jackie hoped so.

She disposed of the first few cases quickly. When her chief court officer, Mike, called the Clark case, Jackie looked up from her computer screen. She motioned to Angela, who was immediately by her side.

“What are those kids doing in here?” Most of the children who appeared before Jackie were of the teenage juvenile delinquent variety, boys and girls 14 or 15 years old who would’ve faced real time in a real prison if they’d been a year or two older and prosecuted as adults. Jackie hardly ever saw the children who were the subjects of the neglect or abuse cases. They were either already in protective custody, or, if it was safe for them to remain living at home while the case proceeded, they were waiting in the daycare on the second floor while the mothers appeared in court. There was no reason to drag them here. Yet here they were, two girls carefully dressed for the occasion in matching denim shorts and purple t- shirts. They looked underweight, but not alarmingly so. Jackie watched as Mike gently led them away from their mother and seated them in the back. He handed them each two chocolate kisses from the glass jar Angela kept on her desk.

“Potential in-court removal. Imminent risk of harm,” Angela said, leaning over to speak in Jackie’s ear.

“Excuse me?” Jackie had seen a lot during her brief time on the bench, but this was something new.

“I spoke to the caseworker from Child Protective Services after the petition was filed this morning. She said that when the school nurse called in the neglect, the agency tried to evaluate the children and assess the situation. The caseworker went to the home on three separate occasions. Each time the mother claimed the kids weren’t home and wouldn’t let her in to look for them.”

“So, what are the kids doing here?” Jackie asked.

“Sometimes, instead of involving the police right away when the parent is uncooperative, the caseworker gives the mother a final chance and directs her to bring the children to court. The mother gets scared and usually complies. Depending on what the caseworker finds when she sees the kids, she has the authority to remove them into protective custody. Here, in the courtroom,” Angela said. “You’ll still have to determine if the removal is indicated down the line. This is a temporary, emergency measure.”

“You’re telling me it’s possible that we’re going to ambush this mother and take her children from her right in front of Ms. Lopez from the Judicial Review Panel?” Jackie swallowed hard, willing herself to stay calm.

“Afraid so, Judge.”

“This can’t be happening…”

As she spoke, the caseworker, flanked by two additional court officers who appeared out of nowhere, escorted the Clark children from the courtroom in stunned silence. Darlene Clark, who may not have completely understood the legal ramifications of what was happening, understood enough. She let out an ear-splitting wail, a blaring distress signal emanating from the deepest core of her being.

That keening—so unnatural and otherworldly—sent Jackie back to her parents’ house on Long Island . . .

She’s ten years old and it’s springtime. On top of a bush that abuts the front porch, a robin has built a nest. The eggs are blue. She understands why the color is called robin’s egg blue, because it has an intensity of identity and a purity she’s never seen anywhere else. Before and after school Jackie checks on the nest, watches the mother sitting protectively on the eggs. A couple of weeks pass and miraculously the tiny baby birds hatch. Now both mother and father go back and forth to the nest, sustaining the young with worms. Jackie loves the birds like they are the pets her mother has never allowed.

One afternoon, Jackie is inside playing the piano. Over the sound of her oft-practiced but never perfected Fur Elise, she hears the most piercing, grief-filled sound. That keening. When she races to the window, a hawk is inches from the nest. The mother bird is inconsolable. It’s a sound that Jackie never would have thought the bird capable of making, a howling so profound. Jackie bangs on the window and flails her arms, shouting at the hawk, “Drop the baby bird, drop him!” The hawk flies away, baby bird in its mouth, while the robin’s death knell continues. In another moment, the mother bird quiets and turns back to the nest. Jackie imagines her finding the strength to comfort the babies that are left after a loss that is unfathomable. The father, attentive when times were good, is nowhere to be seen.

And now this woman in her courtroom was making that same sound.

Sign up to hear Gentin on Thursday night March 10 here, or buy the book on Amazon here or or from Bronx River Books.