Remembering Tom Sobol

- Wednesday, 09 September 2015 16:21

- Last Updated: Thursday, 10 September 2015 15:12

- Published: Wednesday, 09 September 2015 16:21

- Joanne Wallenstein

- Hits: 8139

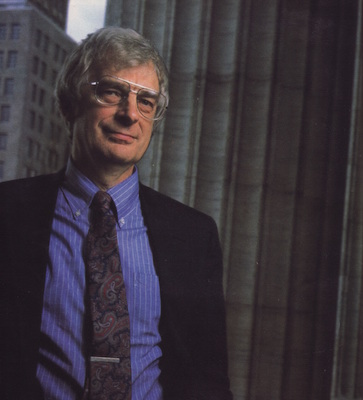

Visionary educator and Scarsdale resident Tom Sobol passed away at the age of 83 on September 3 from complications from Parkinson's Disease. Sobol was well known in Scarsdale where he served as the Superintendent of Schools from 1971 to 1987 before moving on to the state level when he was appointed New York State Commissioner of Education by Governor Mario Cuomo. Sobol was a highly influential educator who championed teachers, students and minorities and believed that local school districts should be given the latitude to decide what's best for their students.

Visionary educator and Scarsdale resident Tom Sobol passed away at the age of 83 on September 3 from complications from Parkinson's Disease. Sobol was well known in Scarsdale where he served as the Superintendent of Schools from 1971 to 1987 before moving on to the state level when he was appointed New York State Commissioner of Education by Governor Mario Cuomo. Sobol was a highly influential educator who championed teachers, students and minorities and believed that local school districts should be given the latitude to decide what's best for their students.

In his memoir, "My Life in School," Sobol traces his humble beginnings from Boston where his father was a railway worker. Sobol attended the Boston Latin School, graduated from Harvard College, earned a graduate degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Education and a doctorate from Teacher's College.

Initially Sobol was a teacher and developed a passion for the profession. In his book he says, "Then I began teaching, and life exploded. I embraced my students with a passion beyond understanding. They and the literature I was teaching were everything to me; I flew into that vast new space winged and exalted. I had never felt such strength, such energy, such fire, never experienced such engagement, such completeness. Some people discover that they have the gift of singing, or dancing, or acting, or healing, or making money. I discovered that I had the gift of teaching. As I used it, I came alive, and it became who I am."

After three years in the army, Sobol taught and served as an administrator in Newton, MA, and Bedford, NY and was named the assistant superintendent for instruction in Great Neck, NY in 1969.

As a child of working class parents, Sobol was not totally comfortable serving privileged children in affluent districts. In a 2007 interview for a publication from Teachers College, Sobol says, "I've spent a lot of ruminating time trying to rationalize much of the work that I did in Scarsdale and, in effect, to apologize to myself for doing it," he says slowly. "Because I was this poor kid-'"the son of Joe Sobolewsky-'"who got a job in a rich community and who was trying to ease his conscience in a way that would do justice to the poor without harming the rich, and who now was supporting that on a statewide level. Who the hell was I for representing Scarsdale, anyway? So that when I became Commissioner, I felt that I was back where I belonged to begin with,'"representing the kids of all of the people and not just those of privilege."

During his tenure as State Commissioner, Sobol designed A New Compact for Learning which set learning standards for students at all grade levels, transferred policy making from bureaucrats to parents and educators and held the state accountable for financing education for students at all economic levels. Sobol was ahead of his time in calling for a de-emphasis on testing which today has resulted in an opt-out movement against state tests. He also appointed a panel of minority politicians and scholars to report on educational opportunities for disadvantaged and minority students in New York State. The report was so scathing that Sobol could not decide whether or not to release it, but ultimately decided to do so.

After resigning from the commissioner position, Sobol went to teach at Columbia's Teacher's College until 2010.

Writing in 2013, Sobol continued to advocate for more local control of education. He wrote, "The State is more likely to achieve its intended effect if it tells people what to achieve instead of telling them how they must achieve it. This straightforward principle applies to education governance just as it does to any other area. Children and communities are different from place to place, and a State should therefore allow local educators to adapt State goals to student-specific and community-specific needs."

Joan Weber, who recently retired as  Assistant Superintendent of Schools after 32 years in Scarsdale, began her tenure here when Dr. Sobol took a chance on a novice and appointed her as Director of Personnel, right after she completed her doctorate. Weber said, "At the time, I did not know that I would be working with an iconic leader in the field." She said that when you worked with Dr. Sobol you knew you were with "a great presence" who laced his inspirational and thoughtful approach with good humor."

Assistant Superintendent of Schools after 32 years in Scarsdale, began her tenure here when Dr. Sobol took a chance on a novice and appointed her as Director of Personnel, right after she completed her doctorate. Weber said, "At the time, I did not know that I would be working with an iconic leader in the field." She said that when you worked with Dr. Sobol you knew you were with "a great presence" who laced his inspirational and thoughtful approach with good humor."

Weber said that Sobol "led with vision and inspiration and empowered and enabled others.... taking everyone to the next level with his high expectations."

Though Sobol found himself in Scarsdale, a district with high achieving students and parent support, he had a real concern for social justice and equity. During his tenure here this compassion led him to attempt to develop a partnership with the Mt. Vernon school district.

According to Weber, during his time in Scarsdale Sobol was extremely inclusive in the decision making process and appointed joint committees of stakeholders to consider initiatives and policy. These collaborative committees were the genesis of the Compact for Learning, which brings parents, teachers and the community together to share responsibility for high-quality education. Sobol took these principles with him to Albany.

Sobol coined the phrase, "Top Down Support for Bottom Up Reform," and believed that though districts should be accountable for educating their students, the curriculum should not be based on testing and assessments. He also championed the idea of the "wrap around community school," in urban impoverished areas, where in addition to educating children the school would provide after-school, social and medical services to the community.

Former Scarsdale Schools Superintendent Michael McGill knew Sobol well, as a colleague and as a friend. We reached out to Dr. McGill and asked him to share some thoughts on his relationship with Sobol and the legacy Sobol leaves behind. Here is what he said:

Former Scarsdale Schools Superintendent Michael McGill knew Sobol well, as a colleague and as a friend. We reached out to Dr. McGill and asked him to share some thoughts on his relationship with Sobol and the legacy Sobol leaves behind. Here is what he said:

1. How did you get to know Tom?

Tom Sobol was one of a handful of acknowledged giants in the field. So even before I met him, I knew him by reputation as a visionary and an intellectual heavyweight. When he became Commissioner, he introduced a series of initiatives collectively called "A Compact for Learning." Tom held meetings around the state for public comment and I went to one of them. Those kinds of events often draw speakers who resist any kind of change, so when I offered a more nuanced critique, Tom riveted his attention on me -- I remember how fiercely focused his gaze was -- and he listened intently. Soon after, he asked me to serve on a Commissioner's advisory council. The rest, as they say,was history.

2. How did Tom affect you?

Tom was a champion of children and particularly as Commissioner, a passionate advocate for educational equity and for public education in our democracy. When he became Commissioner, he periodically appeared on a public radio program where he'd answer reporters' questions. Like another one of the education "greats" of the late 20th century, Ted Sizer, he could offer fresh insight into difficult issues, and his perspective was always highly articulate, informed and authoritative. He had a deep, intuitive understanding of schools and the people in them. When he spoke, he often said what I as an educator thought, and much better than I could have said it. He also was one of a few truly charismatic leaders I've known. When he talked about education as a calling and about its importance to American democracy, teachers and school leaders left feeling better about themselves, feeling they were part of something important and bigger than themselves -- wanting to go forth and be great. And Tom had a sense of humor. He was funny. Those are all qualities I admire and have tried to emulate in my own way.

3. Why, after 28 years, do we seem to be in the same place that we were when Tom was Commissioner.

Tom had a deep understanding of education, schools, and what makes them excellent. As Commissioner, his key premise was that the state should provide "top-down support for bottom-up reform," which was both uncommonly common sense and seriously counter-cultural for an Education Department that had often operated magisterially in the past. He was dealing with a vast bureaucracy in a highly politicized state where the ideological headwinds were increasingly contrary.

At the start, Tom had a narrow window of time to test the idea that truly effective reform develops organically at the bottom with support from above. It was still possible to work on assessment programs that balanced standardized testing with other, more robust, forms of evaluation such as portfolios and oral demonstrations before expert panels. Educational and economic disparities -- and related racial inequality -- were serious problems, but starting in the 1970's, there'd been gains on the National Assessment of Education progress and the achievement gap had begun to close. Considering the importance of resourcing, Tom supported the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, which attempted to provide appropriate funding for children in low income communities.

In the 1990's, however, many politicians, corporate interests and groups like the Business Roundtable, as well as other influentials, were increasingly apt to think that a strategy of accountability, metrics, and competition was the solution to "the problem" of public education -- as if all public schools shared a single problem. In astonishingly short order, that view overtook New York state and its education department, leaving little or no room for the approaches Tom advocated. We've lived with the results for the last three decades: high-stakes testing and narrow, shallow curriculums; charter schools that take resources from regular district schools; an insistence that school is entirely responsible for children's performance, as if economic disparity doesn't matter.

What Tom believed is still true. Since public schooling broadly reflects public values, however, the policies of the last 30 years won't change significantly until numbers of parents and other community members demand it. The recent "opt-out" movement is one sign of dissatisfaction with those policies and what they've wrought. We may all hope and work for the day when his vision of educational equity and excellence becomes reality.

4. What was Tom's legacy?

Well, in addition to everything else I've said, Tom understood that although schooling and fields like medicine and business may be similar in certain ways, education is a unique domain with its own wisdom and unique dynamics. These deserve respect and are not to be tampered with lightly. He also had profound respect for children and for the adults who work with them. He knew that the encounter between teacher and student cannot and should not be reduced to numbers. Not that numbers are completely irrelevant, but that the process is in so many ways a mystery. As he said, the experience is not just about imparting skills and knowledge, but about helping people become fuller and more human, about helping them to feel good about themselves. He had an incisive intelligence and a sometimes cutting wit that valued interesting ideas and good literature and off-center insights. His sense of humanity, his love of creativity, his appreciation for idiosyncrasy, his impatience with sloppy thinking, his refusal to see education primarily in terms of systems, these are among his most important gifts to Scarsdale.