Balancing Act: A Doctor Who Creates Cartoons for The New Yorker

- Monday, 29 January 2018 15:47

- Last Updated: Thursday, 01 February 2018 15:22

- Published: Monday, 29 January 2018 15:47

- Joanne Wallenstein

- Hits: 12855

When we found out that we had a cartoonist for the New Yorker in our neighborhood, and that he was also a doctor, we were curious to learn more about Benjamin Schwartz. He gracioulsy agreed to share his story and some of his artwork below. Enjoy this profile of one of Greenacres most talented and creative residents:

When we found out that we had a cartoonist for the New Yorker in our neighborhood, and that he was also a doctor, we were curious to learn more about Benjamin Schwartz. He gracioulsy agreed to share his story and some of his artwork below. Enjoy this profile of one of Greenacres most talented and creative residents:

So, you grew up in Scarsdale ... When did you discover your love of drawing and art?

I grew up in Greenacres and I honestly can't remember a time when I wasn't doodling.

Who helped to nurture your talent?

My family and friends have always been very supportive of my creative interests. I think my parents recognized fairly early on that cartooning was something more than a hobby for me.

When did you adapt your artistic talent to cartoon drawing?

I've pretty much always been focused on cartooning, so I actually had to figure out the opposite—how to adapt my skills away from cartoon drawing and towards something more lifelike. And that's because cartooning is all about exaggeration and abstraction. You can develop a passable visual vocabulary by studying other cartoons and comics, but to really understand how to cartoon something, you need to know how to draw it realistically first.

What were some of your interests in high school – did you pursue both science and art?

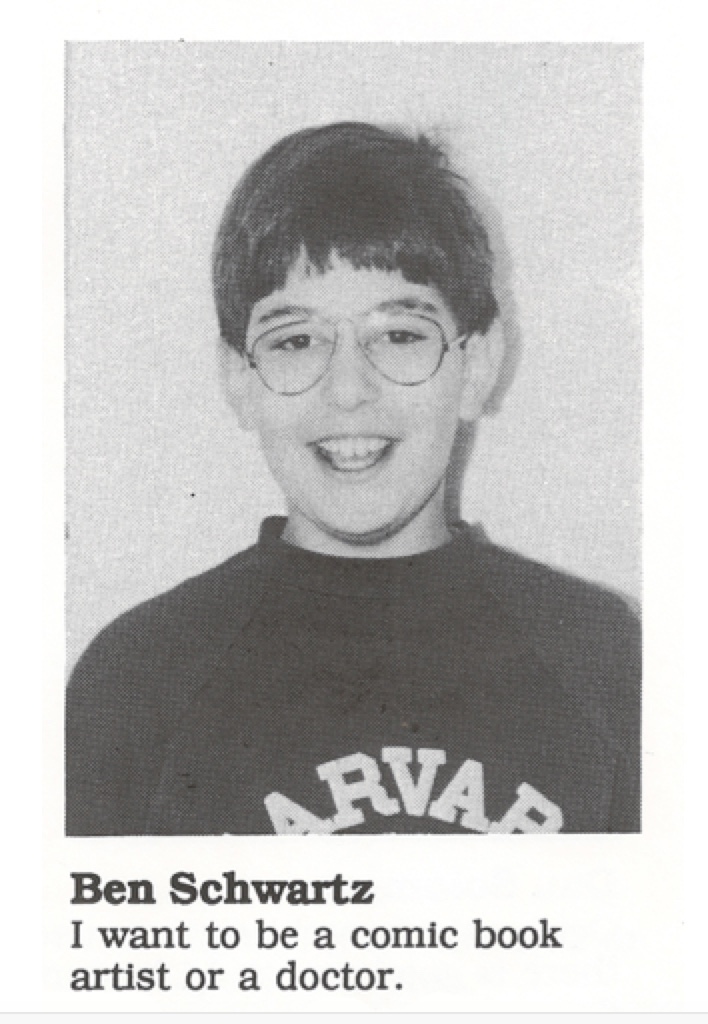

I've always been a bit torn between science and art, even before high school. In  elementary school, my answer to the question, "what do you want to be when you grow up?" was "either a comic book artist or a doctor." (I even have an old elementary school yearbook where it says that in print—see below.)

elementary school, my answer to the question, "what do you want to be when you grow up?" was "either a comic book artist or a doctor." (I even have an old elementary school yearbook where it says that in print—see below.)

In high school, I got to stretch some of my cartooning muscles drawing for the Maroon, the school newspaper.

Having gone through medical school, how did you decide that you also wanted to seriously pursue a career in cartooning?

Well, I always wanted to seriously pursue a career in cartooning, I just didn't think I could; I didn't have confidence in my artistic abilities and I had no idea how to get my foot in the door of the industry. So I put that dream aside and focused on my other dream, to become a doctor.

Medical school wasn't without its challenges, but at the end of the day, it was school, and—thanks in large part to growing up in Scarsdale—I knew how to handle school. When it transitioned into the hectic world of residency, I learned how to handle that, too. And yet, the further I moved along in my training, the more I felt unfulfilled. Medicine was something that interested me, but cartooning was my passion. At some point it dawned on me that if I put as much time and work into pursuing a career in comics as I had in medicine, maybe I could become a good enough artist, and maybe I could figure out how to get my foot in the door.

It sounds like you play a very unique role at Columbia Hospital. Explain what you do.

As an assistant professor in Columbia University Medical Center's Department of Medicine, I teach medical students how to better empathize and communicate with their patients. I do this by having students study and produce art—comic art in particular. My classes are part of a larger program called Narrative Medicine, which started at Columbia but has since spread to medical schools around the country and world. Traditionally, doctors learn to understand illness as a collection of discreet signs and symptoms, yet the way people actually experience illness is narratively—as a story, a chapter in their lives. Art allows students to practice and develop their storytelling skills so that they can eventually provide better, more holistic care to their patients. Here is an example of a cartoon made by one of my students:

How did you apply to have your work published in The New Yorker? How often do you go to the offices and how do they decide what to use?

I found out that Bob Mankoff, the New Yorker's Cartoon Editor (at the time) held weekly open office hours to find new cartooning talent. That kind of direct access to such a major gatekeeper is pretty unheard of, so I knew I had to seize the opportunity. I put together a batch of cartoons and went down to the New Yorker offices to show him. He very graciously looked through them and gave me feedback. He rejected them all but told me I had talent and asked me to come back the next week with more cartoons. So I did, and he rejected those, too--but again he encouraged me to come back. I showed up weekly and got rejected weekly for about six months before I finally broke through and sold my first cartoon. I kept at it, and eventually I became a regular.

The way it works at the New Yorker, each cartoonist sends in around ten original cartoons each week. Between the regular contributors and unsolicited submissions, the Cartoon Editor (now Emma Allen) winds up with a few thousand cartoons on her desk. She whittles that pile down to something more manageable, and then she, along with magazine's head Editor and some others, chooses 15 or so cartoons to be included in the magazine.

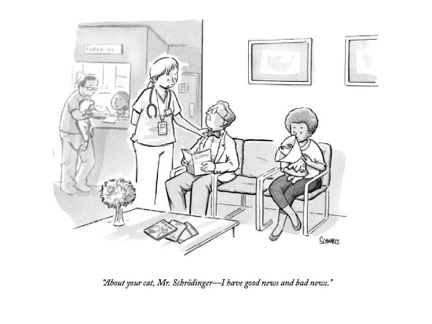

Cartoons get sent in via email these days, so I don't tend to go into the offices very often, though it's nice to touch base with Emma from time to time. Here is my first published New Yorker cartoon:

What inspires your cartoons?

Everything! Being a cartoonist means I'm always looking at the world a little sideways, trying to find the humor in everyday objects and interactions. I never really thought of my cartoons as being particularly personal, but I've noticed that I've been making a whole lot of parenting cartoons since I've become a father.

With Trump in the White House is it more difficult to find humor in politics and everyday interactions?

Yes, for a couple of reasons.

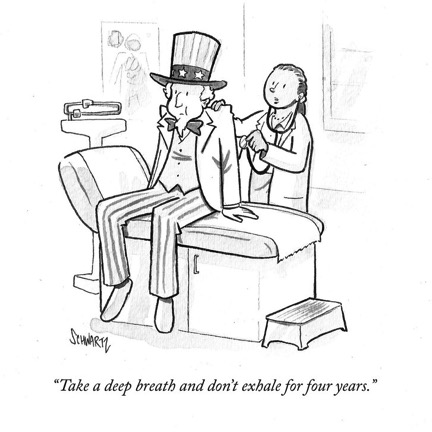

First, I can't say I'm a big fan of his, so most of what I read in the news makes me feel depressed and deflated—not really a great mind-space to create funny cartoons. In fact, one of the toughest challenges I've faced as a cartoonist was coming up with a cartoon the day after he was elected. I was in the middle of a run as the Daily Cartoonist for the New Yorker's website (where I was responsible for producing a topical cartoon every week day), so I had to make something, but the election night outcome left me so numb that it was hard to find any humor in it. I was close to asking my editors for a pass, though I did eventually up with something (see below)

The other challenge with Trump is, even if you want to make jokes, he's already such a heightened, cartoonish figure that it's tough to really top the reality.

Have you ever drawn any cartoons that comment on local issues?

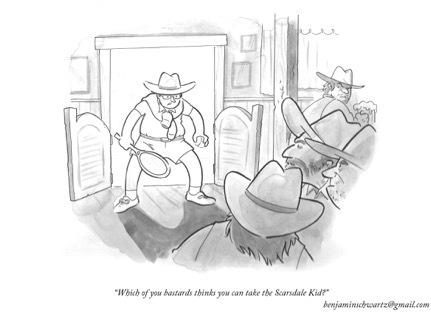

Local as in Westchester? Not really. I once submitted a cartoon that referenced Scarsdale to the New Yorker, but they didn't go for it. It was set in an Old West saloon. An angry-looking stranger has burst through those swinging saloon doors, but he's wearing a sweater vest, short-shorts, and holding a tennis racket instead of a pistol. The caption reads, "Which one of you bastards thinks you can take the Scarsdale Kid?"

Why did you decide to return to Scarsdale?

My wife and I knew we'd probably wind up in the suburbs once we had kids (we had been living in the city). We initially looked all around Westchester, but we kept gravitating towards Scarsdale because of the schools and the proximity to family.

What do you like about living here?

Our house has space to store all my rejected cartoons.

How has it changed since you grew up here? Do you find that children's artistic skills are encouraged?

How has it changed since you grew up here? Do you find that children's artistic skills are encouraged?

So far, it seems remarkably familiar (although the food delivery options are a lot better than I remember), but I almost feel like I can't really answer that question yet; so many of my Scarsdale experiences and memories centered around my education—I don't think I'll really understand how much the place has changed until my kids have entered the school system.

That will probably also give me a better perspective on the towns' encouragement of children's artistic skills, thought between annual events like the Halloween window painting contest and local programs like Young At Art, I can already tell that there's a supportive environment here for kids to make art.